What if they had live-tweeted the Dresden bombings, with the Allies rushing to explain the necessity and then Goebbels in turn tweeting pictures of wounded German children taken in 1915? Thanks to social media, we have become both ambassadors and voyeurs.

July 23, 2014 | Haaretz

There is something bizarre about watching a bloody conflict from afar, play by play, in a barrage of hashtags and video clips and notifications, like some virtual Roman amphitheater.

The luxuries of having a daily peaceful life, choosing to forget that wars rage Elsewhere and Far Away, are of a past era. Now you sit — feeling ludicrous — in a nail salon, in an Italian restaurant, on your veranda, constantly checking news updates and your insides turning with each bit of information.

It’s 2014, and the smell of burning flesh is hand-delivered to your immaculate iPhone.

And you wonder what this kind of dissonance would have looked like in previous wars: What if they had live-tweeted the Dresden bombings, with the Allies rushing to explain the necessity and then Goebbels in turn tweeting pictures of wounded German children taken in 1915? What if the Soviets had produced infographics during the Cold War, and would Jon Stewart have blamed the Soviets for the Americans’ unsophisticated warning system? The Gettysburg Address would be tweeted line by line, Vietnam War soldiers’ families would receive notification of death by WhatsApp, and Babylonian soldiers would post selfies as they waited outside the walls of Jerusalem.

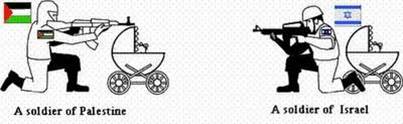

“Home front” is a word which has been redefined in 2014. In some ways, the home front exists wherever the Internet does, an ocean away if need be, and suddenly every one of us is an expert on both military strategy and the topography of Shejaiya too. Social media has made us all at once political commentators and loud-mouthed fools; at once we have become both ambassadors and voyeurs. We are all either absolutely certain that the Israel Defense Forces consistently and always avoids civilian casualties (thanks to the pure objectivity of IDF-produced infographics), or absolutely certain that the IDF consistently and always targets civilians (thanks to Hamas’ eloquent announcements, laced with Syrian stock photos).

The ability to admit ignorance, or humility, is absent here in this speculative blood feud. We are all ready to swear quickly that we really know, yes, we armchair pundits know exactly what is going on in the minds and split-second decisions of 20-year old IDF combat soldiers and Hamas operatives.

It’s bizarre, the way this hyper-connectivity messes with your mind. And it’s wrenching, the way that you no longer recognize yourself as you find yourself whispering Psalms constantly for the sake of people you don’t know, people you’ve never met. In New York, when you first hear of murdered teenagers found in some Hebron basement, you escape your midtown office and find yourself walking towards the United Nations Plaza, and when you stumble upon that wall with the Isaiah quote, you laugh bitterly, softly: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks: Nation shall not lift up sword against nation. Neither shall they learn war anymore.”

Around you, tourists eat ice cream and church bells ring and some girls are taking a selfie and some nametag-toting European bureaucrats enter the plaza laughing about something. And you are walking alone, walking away from these people and away from your newsfeed.

The dissonance is so uncomfortable that I often wonder if I would live with myself more easily if I were in Israel now, rather than here, safely, in my Diaspora cocoon. Some Sages posit that hell isn’t physical torture of fire and brimstone, but rather internal agony alone. Is there some comfort in enduring external conflict, united with one’s people in a bomb shelter somewhere, rather than watching it from afar and suffering from ‘survivor’s’ guilt alone? I wonder.

And it’s in moments like these that your softness dissipates and you grow even more afraid, of both yourself and the world. Your lecture hall debates and university textbooks disappeared as soon as the tunnels appeared. You’ve forgotten how you smiled victoriously to your friends as you lambasted Western imperialism, and suddenly everything else has become irrelevant, your cold calculations and calm rationale and journal subscriptions and newspaper affiliations are forgotten — and you don’t recognize yourself when you suddenly find yourself crying randomly or swearing that you’ll do whatever it takes to hold onto this Land of ours, yes, that you will go for thyself from thy birthplace and from thy home and move there to that scorching cursed country, and that your own children, your very own offspring, will one day build settlements too if that’s what it takes, whatever it takes dear God, and you are caught in this blur of anguish and zeal, this ancient emotion you were sure had been buried long ago in those same textbooks – and does that rage make you any less human? Or does it make you more human? Yes. This – this is the raw and uncomfortable beginning of madness, the demons one fights deep within.

How is it so all-consuming?

And that “Red Alert” app — I regretted downloading it after a few hours but still can’t bring myself to delete it. Why do I feel a need to know every time that a siren goes off in Israel? What kind of masochistic people am I a part of, where this is considered normal? Do other people have this awfully personal way in which distant conflicts grip their every moment and make it difficult to wake up in the morning? Is that normal — do Syrian-Americans also have a system to follow Assad’s attacks? Have Ukrainian expats built an app which notifies them of every separatist gunshot in Donetsk?

The way in which the last weeks’ events have gripped the imagination and fears of Diaspora Jewry, too: I am not sure one can articulate the darkness which has come over some of us now, even here, even this far away.

It comes over you when you’re in the street, on the subway, in a crowd, and you suddenly feel terribly alone because the businessmen next to you are discussing yesterday’s staff meeting – while you’re sitting there for an hour driving your mind in crazed circles about what proportionate warfare means after all, and whose victim narrative is more right, and you’re trying to convince yourself that the world can’t possibly hate you, no, that’s a genetic complex you’ve inherited but you’ll get over it soon. The occasional Parisian synagogue and Berlin street protest aside, surely they don’t hate you — but why is it that when you walk in New York in your unmistakably Orthodox uniform, that you are tempted to quicken your pace, and that you have reverted to careful glances? Perhaps it is because it has become increasingly difficult to give the world the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps because you trust less and less, as the world gathers to deny Israeli citizens the right to sleep peacefully, as tunnels are dug into kibbutz playgrounds. Or perhaps because you have long ago shut up with your inculcated hasbara education and thrown away your “Myths and Facts” charts, and instead learned to tighten your jaw and stop trying to defend the morality of our army – and now, you simply, quietly, humbly, bow your head in gratitude to their sacrifice.

The words of Moshe Dayan from 1956 continue to ring in my mind, definitively: “This is the fate of our generation, that is our choice – to be ready and armed, tough and hard – or else the sword shall fall from our hands and our lives will be cut short.”

Or older, more terrible, words: “By your blood you shall live.”

There was a time, just a few weeks and lifetimes ago, when I believed that this fate was for previous generations – that my generation would indeed be different, that we would have other choices at our disposal. But that promise, of a different and more peaceful fate – we found that promise. We found it somewhere in a Hebron basement, eighteen days too late, riddled with bullets.

The luxuries of having a daily peaceful life, choosing to forget that wars rage Elsewhere and Far Away, are of a past era. Now you sit — feeling ludicrous — in a nail salon, in an Italian restaurant, on your veranda, constantly checking news updates and your insides turning with each bit of information.

It’s 2014, and the smell of burning flesh is hand-delivered to your immaculate iPhone.

And you wonder what this kind of dissonance would have looked like in previous wars: What if they had live-tweeted the Dresden bombings, with the Allies rushing to explain the necessity and then Goebbels in turn tweeting pictures of wounded German children taken in 1915? What if the Soviets had produced infographics during the Cold War, and would Jon Stewart have blamed the Soviets for the Americans’ unsophisticated warning system? The Gettysburg Address would be tweeted line by line, Vietnam War soldiers’ families would receive notification of death by WhatsApp, and Babylonian soldiers would post selfies as they waited outside the walls of Jerusalem.

“Home front” is a word which has been redefined in 2014. In some ways, the home front exists wherever the Internet does, an ocean away if need be, and suddenly every one of us is an expert on both military strategy and the topography of Shejaiya too. Social media has made us all at once political commentators and loud-mouthed fools; at once we have become both ambassadors and voyeurs. We are all either absolutely certain that the Israel Defense Forces consistently and always avoids civilian casualties (thanks to the pure objectivity of IDF-produced infographics), or absolutely certain that the IDF consistently and always targets civilians (thanks to Hamas’ eloquent announcements, laced with Syrian stock photos).

The ability to admit ignorance, or humility, is absent here in this speculative blood feud. We are all ready to swear quickly that we really know, yes, we armchair pundits know exactly what is going on in the minds and split-second decisions of 20-year old IDF combat soldiers and Hamas operatives.

It’s bizarre, the way this hyper-connectivity messes with your mind. And it’s wrenching, the way that you no longer recognize yourself as you find yourself whispering Psalms constantly for the sake of people you don’t know, people you’ve never met. In New York, when you first hear of murdered teenagers found in some Hebron basement, you escape your midtown office and find yourself walking towards the United Nations Plaza, and when you stumble upon that wall with the Isaiah quote, you laugh bitterly, softly: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks: Nation shall not lift up sword against nation. Neither shall they learn war anymore.”

Around you, tourists eat ice cream and church bells ring and some girls are taking a selfie and some nametag-toting European bureaucrats enter the plaza laughing about something. And you are walking alone, walking away from these people and away from your newsfeed.

The dissonance is so uncomfortable that I often wonder if I would live with myself more easily if I were in Israel now, rather than here, safely, in my Diaspora cocoon. Some Sages posit that hell isn’t physical torture of fire and brimstone, but rather internal agony alone. Is there some comfort in enduring external conflict, united with one’s people in a bomb shelter somewhere, rather than watching it from afar and suffering from ‘survivor’s’ guilt alone? I wonder.

And it’s in moments like these that your softness dissipates and you grow even more afraid, of both yourself and the world. Your lecture hall debates and university textbooks disappeared as soon as the tunnels appeared. You’ve forgotten how you smiled victoriously to your friends as you lambasted Western imperialism, and suddenly everything else has become irrelevant, your cold calculations and calm rationale and journal subscriptions and newspaper affiliations are forgotten — and you don’t recognize yourself when you suddenly find yourself crying randomly or swearing that you’ll do whatever it takes to hold onto this Land of ours, yes, that you will go for thyself from thy birthplace and from thy home and move there to that scorching cursed country, and that your own children, your very own offspring, will one day build settlements too if that’s what it takes, whatever it takes dear God, and you are caught in this blur of anguish and zeal, this ancient emotion you were sure had been buried long ago in those same textbooks – and does that rage make you any less human? Or does it make you more human? Yes. This – this is the raw and uncomfortable beginning of madness, the demons one fights deep within.

How is it so all-consuming?

And that “Red Alert” app — I regretted downloading it after a few hours but still can’t bring myself to delete it. Why do I feel a need to know every time that a siren goes off in Israel? What kind of masochistic people am I a part of, where this is considered normal? Do other people have this awfully personal way in which distant conflicts grip their every moment and make it difficult to wake up in the morning? Is that normal — do Syrian-Americans also have a system to follow Assad’s attacks? Have Ukrainian expats built an app which notifies them of every separatist gunshot in Donetsk?

The way in which the last weeks’ events have gripped the imagination and fears of Diaspora Jewry, too: I am not sure one can articulate the darkness which has come over some of us now, even here, even this far away.

It comes over you when you’re in the street, on the subway, in a crowd, and you suddenly feel terribly alone because the businessmen next to you are discussing yesterday’s staff meeting – while you’re sitting there for an hour driving your mind in crazed circles about what proportionate warfare means after all, and whose victim narrative is more right, and you’re trying to convince yourself that the world can’t possibly hate you, no, that’s a genetic complex you’ve inherited but you’ll get over it soon. The occasional Parisian synagogue and Berlin street protest aside, surely they don’t hate you — but why is it that when you walk in New York in your unmistakably Orthodox uniform, that you are tempted to quicken your pace, and that you have reverted to careful glances? Perhaps it is because it has become increasingly difficult to give the world the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps because you trust less and less, as the world gathers to deny Israeli citizens the right to sleep peacefully, as tunnels are dug into kibbutz playgrounds. Or perhaps because you have long ago shut up with your inculcated hasbara education and thrown away your “Myths and Facts” charts, and instead learned to tighten your jaw and stop trying to defend the morality of our army – and now, you simply, quietly, humbly, bow your head in gratitude to their sacrifice.

The words of Moshe Dayan from 1956 continue to ring in my mind, definitively: “This is the fate of our generation, that is our choice – to be ready and armed, tough and hard – or else the sword shall fall from our hands and our lives will be cut short.”

Or older, more terrible, words: “By your blood you shall live.”

There was a time, just a few weeks and lifetimes ago, when I believed that this fate was for previous generations – that my generation would indeed be different, that we would have other choices at our disposal. But that promise, of a different and more peaceful fate – we found that promise. We found it somewhere in a Hebron basement, eighteen days too late, riddled with bullets.