Friday, February 28, 2020

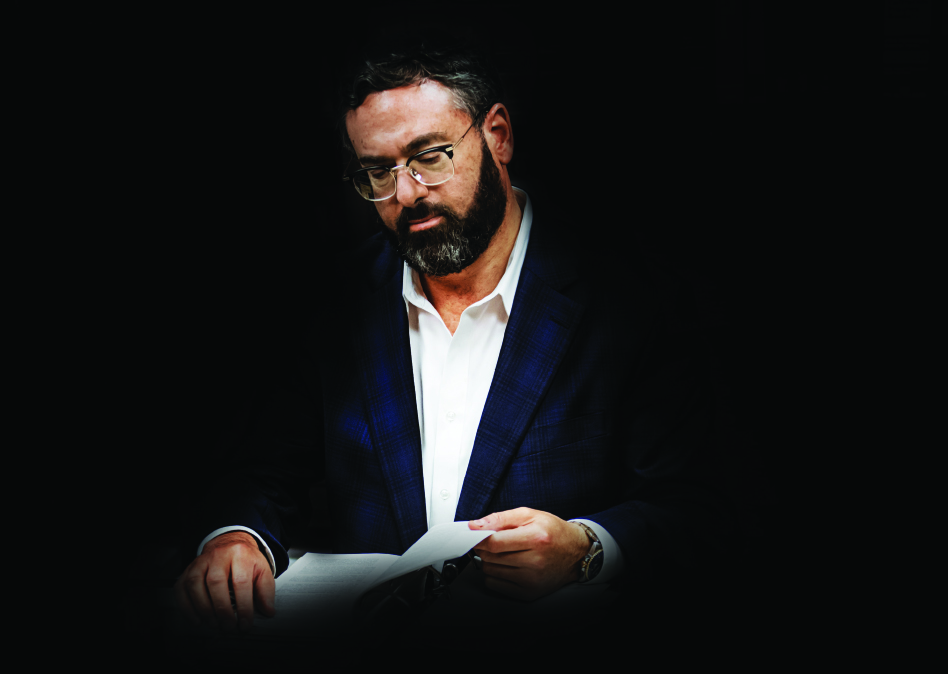

BCC schmoozing with his cousin, Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Hager, son of the Vizhnitzer Rebbe of Monsey and son-in-law of the Skverer Rebbe of New Square NY, at the Los Angeles reception of Mosdos Vizhnitz.

BCC schmoozing with his cousin, Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Hager, son of the Vizhnitzer Rebbe of Monsey and son-in-law of the Skverer Rebbe of New Square NY, at the Los Angeles reception of Mosdos Vizhnitz.

BCC’S mother's Chassidic lineage intersects and stems from Rabbi Chaim Hager of Ottynia (the Tal Chaim) (1863-1931) who was a brother of Rabbi Yisroel Hager, the 3rd Rebbe of Vizhnitz (the Ahavas Yisroel) (1860-1936); who was the son of Rabbi Baruch Hager, the 2nd Rebbe of Vizhnitz (the Imrei Baruch) (1845-1892); who was the son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, the 1st Rebbe of Vizhnitz (the Tzemach Tzadik) (1830-1884) (son in law of Yisroel of Ruzhin); who was the son of Rabbi Chaim Hager of Kosov (the Toras Chaim); who was the son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager of Kosov (the Ahavas Shalom); who was the son of Rabbi Yaakov Koppel Likover (disciple of the Baal Shem Tov)

Photo credit Rabbi Yisrael Gelb

(Think about it: but for, WWII, BCC would probably be looking just like his Chassidisher cousins)

1. My Grandfather, Rabbi Baruch Hager, zt'l (1899-1942).

My mother's father was Rabbi Baruch Hager of Horodenka, ABD Cozmeni, Bukovina from 1936 and then Dayan in Czernowitz, born in 1899 and died of typhus in the work camp in Warchovka, Transnitra Concentration Camp in 1941, married in 1922 to his first cousin Miriam, daughter of R. Shraga Feivel Hager of Zaleszczyki (Zalischik). He was very active in the Mizrachi movement and Zeire Mizrachi and was President of the Torah V’Avodah. She remarried in 1954/5 to R. Moshe Zvi Twersky, Admur Tolna-Philadelphia.

Rabbi Baruch Hager was the son of Rabbi Yechiel Michel Hager, Admur Horodenka from 1892 on his father’s death, born in 1872 and died of typhus in the work camp in Warchovka, Transnitra Concentration Camp in 1941 (as did his son Baruch), married his niece, Bluma Reizel, daughter of R. Haim Hager of Ottynia. He was one of the sons of the Imrei Baruch, he was appointed Rebbe (as were his brothers), after his father's petira on 20 Kislev 1892. Rav Yechiel Michel moved to Horodenka, to succeed his brother, Rav Shmuel Abba, who passed away childless in 1895. He married the daughter of his older brother, Rav Chaim (Rebbe in Antiniya). During World War I, he escaped to Chernowitz and served as Rebbe to the many Vizhnitz Chassidim there. He had one son, Baruch, who was later appointed Dayan in Chernowitz. After Sukkos of 1941, he was among 5000 Jews who were deported to Transnistria, and area in southwestern Ukraine, between the Dniester River ("Nistru" in Romanian) and the Bug River, north of the Black Sea. Also on that transport was Rav Aharon of Boyan, who came down with typhus and was niftar on 13 or 14 Cheshvan. Both Rav Yechiel Michel and his son Baruch came down with typhus in the work camp in Warchovka and died there.

2. My Great-Grandfather, Rabbi Yechiel Michel Hager of Horodenka, zt'l (1872-1942).

Rabbi Yechiel Michel Hager was the son of Rabbi Baruch Hager, 2nd Vizhnitzer Rebbe (the "Imrei Baruch") and Zipora Hagar. His brothers were Rabbi Yisroel Hager, 3rd Vizhnitz Rebbe; R' Chaim Hager, Admur Ottynia (Itinia); R' Moshe Hager, Admur Shatz; R' Shmuel Abba Hager of Kolomyja-Horodenka; R' Yitzhak Yaakov Dovid Hager of Storozhinets-Vienna.

3. My Great-Great Grandfather, Rabbi Baruch Hager, 2nd Vizhnitzer Rebbe, the "Imrei Baruch" was the son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, 1st Vizhnitzer Rebbe and Miriam Hager (1845-1892).

4. My Great-Great-Great Grandfather, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, was 1st Vizhnitzer Rebbe (the "Tzemach Tzaddik") (1830-1884).

5. My Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather, was Rabbi Chaim Hager of Kosow and Tzipora Hager (the ""Toras Chaim") (1795-1854).

6. My Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather, was Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, of Kosov (the "Ahavas Shalom") (1768-1825).

7. My Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather, was Rabbi Yacov-Kopel [Chassid of Kolomaya] Hager and Chaya Hager (1730-1787) and was a Talmid of the Baal Shem Tov.

BCC’S mother's Chassidic lineage intersects and stems from Rabbi Chaim Hager of Ottynia (the Tal Chaim) (1863-1931) who was a brother of Rabbi Yisroel Hager, the 3rd Rebbe of Vizhnitz (the Ahavas Yisroel) (1860-1936); who was the son of Rabbi Baruch Hager, the 2nd Rebbe of Vizhnitz (the Imrei Baruch) (1845-1892); who was the son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, the 1st Rebbe of Vizhnitz (the Tzemach Tzadik) (1830-1884) (son in law of Yisroel of Ruzhin); who was the son of Rabbi Chaim Hager of Kosov (the Toras Chaim); who was the son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager of Kosov (the Ahavas Shalom); who was the son of Rabbi Yaakov Koppel Likover (disciple of the Baal Shem Tov)

Photo credit Rabbi Yisrael Gelb

(Think about it: but for, WWII, BCC would probably be looking just like his Chassidisher cousins)

1. My Grandfather, Rabbi Baruch Hager, zt'l (1899-1942).

My mother's father was Rabbi Baruch Hager of Horodenka, ABD Cozmeni, Bukovina from 1936 and then Dayan in Czernowitz, born in 1899 and died of typhus in the work camp in Warchovka, Transnitra Concentration Camp in 1941, married in 1922 to his first cousin Miriam, daughter of R. Shraga Feivel Hager of Zaleszczyki (Zalischik). He was very active in the Mizrachi movement and Zeire Mizrachi and was President of the Torah V’Avodah. She remarried in 1954/5 to R. Moshe Zvi Twersky, Admur Tolna-Philadelphia.

Rabbi Baruch Hager was the son of Rabbi Yechiel Michel Hager, Admur Horodenka from 1892 on his father’s death, born in 1872 and died of typhus in the work camp in Warchovka, Transnitra Concentration Camp in 1941 (as did his son Baruch), married his niece, Bluma Reizel, daughter of R. Haim Hager of Ottynia. He was one of the sons of the Imrei Baruch, he was appointed Rebbe (as were his brothers), after his father's petira on 20 Kislev 1892. Rav Yechiel Michel moved to Horodenka, to succeed his brother, Rav Shmuel Abba, who passed away childless in 1895. He married the daughter of his older brother, Rav Chaim (Rebbe in Antiniya). During World War I, he escaped to Chernowitz and served as Rebbe to the many Vizhnitz Chassidim there. He had one son, Baruch, who was later appointed Dayan in Chernowitz. After Sukkos of 1941, he was among 5000 Jews who were deported to Transnistria, and area in southwestern Ukraine, between the Dniester River ("Nistru" in Romanian) and the Bug River, north of the Black Sea. Also on that transport was Rav Aharon of Boyan, who came down with typhus and was niftar on 13 or 14 Cheshvan. Both Rav Yechiel Michel and his son Baruch came down with typhus in the work camp in Warchovka and died there.

2. My Great-Grandfather, Rabbi Yechiel Michel Hager of Horodenka, zt'l (1872-1942).

Rabbi Yechiel Michel Hager was the son of Rabbi Baruch Hager, 2nd Vizhnitzer Rebbe (the "Imrei Baruch") and Zipora Hagar. His brothers were Rabbi Yisroel Hager, 3rd Vizhnitz Rebbe; R' Chaim Hager, Admur Ottynia (Itinia); R' Moshe Hager, Admur Shatz; R' Shmuel Abba Hager of Kolomyja-Horodenka; R' Yitzhak Yaakov Dovid Hager of Storozhinets-Vienna.

3. My Great-Great Grandfather, Rabbi Baruch Hager, 2nd Vizhnitzer Rebbe, the "Imrei Baruch" was the son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, 1st Vizhnitzer Rebbe and Miriam Hager (1845-1892).

4. My Great-Great-Great Grandfather, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, was 1st Vizhnitzer Rebbe (the "Tzemach Tzaddik") (1830-1884).

5. My Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather, was Rabbi Chaim Hager of Kosow and Tzipora Hager (the ""Toras Chaim") (1795-1854).

6. My Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather, was Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager, of Kosov (the "Ahavas Shalom") (1768-1825).

7. My Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather, was Rabbi Yacov-Kopel [Chassid of Kolomaya] Hager and Chaya Hager (1730-1787) and was a Talmid of the Baal Shem Tov.

Labels:

Baruch C. Cohen,

Vizhnitz

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

Behaving like a Mentch

Behaving like a Mentch

Although I have never met him, Orthodox Los Angeles attorney Baruch Cohen and I have a shared experience that we would not wish on our worst enemy. We both lost children to a rare form of cancer known as Ewing’s Sarcoma. He a lost a daughter. I lost a grandson. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to lose a child. The pain must be indescribable. But I can tell you that losing a grandchild is not easy either. (R’ Baruch talks about his personal experience in a Mishpacha Magazine article.)

Thankfully we have more than just that in common. We both have an almost visceral hatred for Chilul HaShem. Especially the kind that is the result of poorly developed sense of ethics when it comes to the secular world in which we live. This has unfortunately manifested itself more times than I can count in recent years. So often that I have stopped counting.

More often than not this happens by way of cheating the government out of money. Whether it is laundering criminally obtained funds via an elaborate charity system; or avoiding federal taxes through inflated charitable donations – 90% of which are kicked back; or using funds the government earmarked for one thing for something else; or using other people’s social security numbers to divert payments to themselves… you name it. If there is a way to cheat the government, it has probably been tried.

I have written about many of these things and have condemned them all. They were legally wrong and the perpetrators knew it. But in some cases they saw nothing wrong with it morally and committed those crimes because they thought they could get away with. I recall one fellow I know who now sits in prison making an offhand remark that government clerks manning the system are so ‘dumb’ that stealing from the government would be a near risk free enterprise. He found out that those clerks weren’t so dumb after all. And in fact they are a lot smarter than he is.

That said, fear of being caught should not be what motivates anyone from committing a crime. Even now where prison reform is a bit more favorable to those who commit those crimes. It ought to be our sense of morals and ethics… our fear of creating a Chilul HaShem. Not fear of getting caught.

This is where Jewish education seems to have failed. Let me hasten to add that I am not castigating every yeshiva or elementary school. I am absolutely convinced that many schools do teach ethics and try mightily to teach their students ethical behavior. That in fact was my own personal experience. I had many teachers like that and one in particular that was an exemplar of ethical and moral behavior in every respect.

But I fear that are many instances where there has not been enough of that. Not at home where it should begin. And not in school. In fact there are some schools that practically teach the opposite. I recall listening to a recording of a Hashkafa Shiur where a Rebbe in a popular Yeshiva high school vilified virtually all non Jews to such an extent, that one might come out believing that it is practically a Mitzvah to take advantage of them in any way you could – as long as you didn’t get caught! It sickened me, to say the least!

This is where Baruch Cohen comes in. His Hashkafos are Charedi in the mold of the Chofetz Chaim Yeshiva. For which I have a soft spot. They are among the finest of Yeshivos - producing role models of behavior. Their students become Talmidei Chachamim with a highly developed sense of morals and ethics. I received the following note from him which speaks for itself:

This past x-mas, I had the opportunity... to address the Boys Division of Valley Torah High School (VTHS) on “Killer Litigation Strategies for Lawsuits, Business and Life.” (Avoiding Chillul Hashems). Below and enclosed is the the outline of the speech. It was based on many Youtube speeches that I heard by criminal defense attorney Ben Brafman on the issue.

I used various headlines of Chillul Hashem in the powerpoint presentation so that the boys and the rabbonim experience the "cringe factor."

It was a huge hit; the boys didn't want to leave afterwards and the hands were all raised with questions. This important topic totally gripped the audience. Your outstanding blog on this issue was a major inspiration.

This was followed by another note which said the following:

VTHS Dean and Rosh Yeshivah Rabbi Avrohom Stulberger said: "We need more voices like that of Baruch Cohen. Frum attorneys, yeshiva graduates, a talmid chochom to be role models to our kids. Too often it's only rabbonim who we look to as role models. We need more baal habatim who are shtark bnei torah to set examples to our kids. To know from the secular world, right from wrong. To speak from the trenches of the secular world, how to behave like a mentsch."

And that was followed by still another note from R’ Baruch personally:

Frum Baal habatim who have been koveah itim on a serious level all of our lives need to be seen as role models for our youth. Our society’s 2-tier system that the ideal is learning in kollel and the not-so-ideal is to work for a living is simply wrong and misguided. It turns off many and gives them an inferiority complex if they pursue honest parnassah that somehow they failed the system.

Like I said, we have a lot in common. What he has done in LA should be the model adopted by all days schools and Yeshiva high schools. I hope that officials at Torah U’Mesorah are listening. What follow is the above-mentioned outline of his talk.

1. The World Does Not like Jews - we do not need to encourage more people to dislike us

2. Wearing a Yarmulkeh - carries with it an extra measure of responsibility

3. We Must Be More Honest - more careful, more courteous & more prudent

4. When We Screw-Up, it Gets Magnified - the “Cringe Factor” (ie., Frum Slumlords)

5. Having Good Intentions Is Not a Legitimate Excuse - for Breaking the Law

6. Bad Behavior for a Good Cause - a lie for a good reason & a Mitzvah is still a lie

7. The US Government Is Not the Enemy - we’re not in Europe during WW-II8. We Cannot Pick & Choose the Rules We Live by - no smorgasbord Judaism

Baruch Cohen’s 14 Rules for the American Orthodox Jew:

1. Keep Your Word - do what you what you say you're going to do

2. Document Everything - confirm everything in writing

3. Follow the Rules - be a law-abiding citizen - know the laws - serve on a Jury

4. Don't Think You're Smarter than the Law & Won't Get Caught - you will

5. You’re Not Right Because You’re Orthodox - you’re right because you’re honest

6. Establish Credibility - admit when you're wrong

7. Listen to Your Internal Compass - if it sounds to good to be true, it is;

8. Consult Before Taking Action - not after

9. Believe in Yourself, Act with Courage & Confidence - but never with arrogance

10. Stop Being Nosy - “but I’m just asking”

11. Give Unconditionally - with no expectation of anything in return

12. Insert Bais Din Arbitration Clauses in Your Contracts - believe in our Torah

13. Stand up for Judaism & Eretz Yisroel - never apologize about both

14. Pause, Before Pushing “Send” on Emails and Texts - it could save your life

Labels:

Baruch C. Cohen

BORN OF GRIEF, By Baila Rosenbaum | MISHPACHA MAGAZINE, DECEMBER 25, 2019

BORN OF GRIEF, By Baila Rosenbaum | MISHPACHA MAGAZINE, DECEMBER 25, 2019

The Torah tells us that after the death of Aharon’s two sons, “Vayidom Aharon — and Aharon was silent.” “But what about his wife?” asks Baruch. How did she cope? What does the Torah tell us about her life after this tragedy?

It wasn’t so long ago that Baruch Cohen and his family, content New York transplants to Los Angeles, were living a life of innocence. Baruch ran a successful high-powered litigation law practice and the four Cohen children attended the local yeshivos and Bais Yaakov. A product of over six years of beis medrash and kollel, Baruch was kovei’a itim and his learning schedule included Mishnah Berurah yomi and the daf. Life was good.

He was going strong and two-and-a-half years into daf yomi when, within days of 9/11, the family’s upwardly mobile life experienced its own ground zero. The Cohens’ daughter, 15-year-old Hindy, was diagnosed with a pediatric cancer called Ewing’s sarcoma and the Cohens’ world changed irrevocably.

“I had to juggle an active law practice, we had to take care of our other children, deal with the emotional trauma of pediatric oncology, arrange medical care, babysitters, Chai Lifeline, Bikur Cholim — the works — while avoiding the gravitational pull of the black hole of anxiety, fear, and depression,” Baruch remembers. Though he was a very active learner before the crisis, his learning fell by the wayside as Hindy’s battle took center stage.

Hindy faced her illness with grace and courage, but succumbed after two-and-half-years, leaving the family bereft and grieving. Her passing demanded a new set of existential challenges for Baruch and would send him on a unique journey in his learning.

“During the shivah,” he remembers, “people would express meaningless clichés and drop platitudes that were almost repulsive to me. Phrases like ‘ein milim,’ there are no words. What did that mean? There is a word for everything in the Torah. Torah is timeless, it has messages for everybody. How could it be that there were no words in the Torah for a bereaved parent?”

Certain that there must be words in the vastness of Torah that would speak to his situation, Baruch set out to find them.

Back when Hindy had been healthy, Baruch had kept to a daily regimen of Gemara learning. During her illness, he dropped out of learning entirely. Now, after her tragic death, as he grappled with the new contours of his world of bereavement, his passion for learning was reignited — with a new focus on the weekly sedra.

When learning the parshah, Baruch found that he was listening through the ears of a bereaved parent. “A baal nisayon breathes different oxygen than everyone else. He processes things through a different lens. I was perceiving things differently and started learning Torah differently.”

Reading about Yaakov and Yosef’s reunion in Mitzrayim the mefarshim say that Yosef cried, but Yaakov did not cry. Rashi says he was reciting Krias Shema. “What I understood from that was, of course he couldn’t cry! He was hyperventilating. He was face to face with the son whose death he had mourned.”

Looking through what Baruch describes as “tainted lenses” led him on a quest to find an understanding of the Torah that would provide him with consolation, connection, and, ultimately, enlightenment. He started learning again — but differently, on his terms. “I reinvented myself,” he says.

He began to note every tragedy and researched the mefarshim to understand how Torah personalities coped with their challenges. Kayin killed Hevel, now Adam and Chavah were bereaved parents. What does the Torah tell us about how they reacted? Unlike material about grief and mourning available on the broader market, Baruch’s learning was on a level that resonated with the well-seasoned ben Torah and kollel avreich — using every commentary in the Mikraos Gedolos, the Midrash Rabbah, the Yalkut Shimoni, and other high-level sources, where he sought to discover how our forefathers coped with tragedy.

His studies expanded and he started researching gedolei Yisrael, reading their letters and seforim to discover how they coped with challenges. The result: a 500-page compilation of his writings, correspondences, and helpful articles he’s accumulated over the years, which he shares as chizuk for those in need, titled Reb Yochanon’s Bone: Chizuk for the Bereaved Parent (referred to by several gedolim as “the encyclopedia of nechamah”).

Baruch’s learning morphed into community-wide mussar vaadim (i.e., Shaar Habitachon of Chovos HaLevavos; Shaar Hasimchah and Shaar Ha’anavah of Orchos Tzaddikim; Shaar Hanekius of Mesillas Yesharim; and Bilvavi Mishkan Evneh) and a yearly public speech given on Hindy’s yahrtzeit in which he shares insights into grieving and healing. In these speeches, Baruch takes a topic that fascinates him and dives in. That means delving into myriad mefarshim, camping out in the kollel late at night, following leads, calling rabbanim, and attacking the issue like a legal researcher would.

The topics he chooses are not outside the mainstream, but they are beyond the typical perspective; he describes them as “the stuff wedged in between the cracks of the sidewalk, the space between the words, or the pause in between the musical notes.” For example, the Torah tells us that after the death of Aharon’s two sons, “Vayidom Aharon — and Aharon was silent.”

“But what about his wife?” asks Baruch. How did she cope? What does the Torah tell us about her life after this tragedy?

In another example, Baruch cites that a navi needs to be b’simchah when he receives and conveys a prophecy. So how, then, did Yirmiyahu write Eichah? He could not have been in a joyous state of mind when reliving the Churban! Most of us would never have thought of this question, but Baruch discovered that many others already have — including the Chazon Ish, Rav Yehonasan Eybeschutz, Yam Hamelach, and the Ben Ish Chai.

Questions like these coupled with Baruch’s exhaustive research have culminated in magnificent articles and presentations that Baruch shares, both by speaking publicly and in his writing. He is the author of Grieving and Healing in the Prism of Torah: Parents’ Spiritual Guide through Pain and Grief, a book devoted to bringing hope to the bereaved and help them reclaim happiness from tragedy.

Today Baruch is a steady address for speaking requests and it’s rare that a nichum aveilim visit is not met with a request for tender words of chizuk and consolation. But Baruch Cohen is not a man who lives in sadness. Whereas tragedy brings pain and profound sadness, he resists thoughts that may lead to depression and attains nechamah from the fact that, though his daughter has died, her neshamah is everlasting.

“I feel a close connection to Hindy’s neshamah. I have a fidelity and awareness to her neshamah that I always try to honor. It’s a mindset and it brings me tremendous consolation. I don’t carry myself as defeated or destroyed, it’s not in my DNA.”

He reasoned that Hashem wanted him to have this experience for a specific purpose. “So where does this pain lead me?” he asked himself. “What middos are surfacing? How can I inspire others?”

Baruch Cohen’s focus is on grieving rather than healing, because it’s a critical stage that is typically overlooked but can’t be bypassed. This realization has brought his learning to a rare and unusual level that has provided insight not only to those who share his unique “lenses,” but to many others seeking growth in Torah and hashkafah.

“My learning now is my own charted path,” he says. “I’m learning on a high level b’iyun, sourcing 20 to 30 mefarshim on a topic. But I’ve redefined myself and my approach to learning. I’m not learning the regular topics; I’m finding and sharing gems of insights normally not recognized.

“Yes, my focus is on grief,” he admits, “but that’s not because I’m mired in sadness. It’s because that grief became my channel to a learning regimen that motivates and inspires me. We all have difficulties in our lives, and our job is to remember that the ‘obstacle is the way.’ Those seeming obstacles often point us in the direction we need to grow closer to Hashem.”

(Originally featured in ‘One Day Closer’, Special Supplement, Chanuka/Siyum HaShas 5780)

Labels:

Baruch C. Cohen,

Hindy Cohen

WHOLE BROKEN VESSELS, By Barbara Bensoussan | MISHPACHA MAGAZINE, JULY 18, 2018

WHOLE BROKEN VESSELS, By Barbara Bensoussan | MISHPACHA MAGAZINE, JULY 18, 2018

“Suddenly you’re breathing a different oxygen than everyone else. I used to flip past the Chai Lifeline ads in magazines with pictures of sick kids — I never imagined it could concern me!”

Baruch C. Cohen is a tall man with a commanding presence, the sonorous voice of a stage actor, and a trial lawyer’s way with words. His law office, on the ninth floor of a swanky professional building on Wilshire Drive, affords a sweeping view of Los Angeles, with downtown at one end and the Pacific Coast at the other. The walls are adorned with framed degrees, awards, and news articles in which he’s been featured.

Everything in this immaculate, gleaming office speaks to prestige and success, and Cohen presents as an alpha-male lawyer, an intense and forceful advocate who knows what he wants to achieve and will go after it tenaciously. He has been described by others as a “pit bull” in courtroom battles, and is equally aggressive about defending Israel’s right to exist, authoring a blog entitled American Trial Lawyers in Defense of Israel.

Yet despite his powerful personality, Cohen was brought to his knees some 14 years ago when tragedy struck his family. His oldest child, Hindy, was diagnosed with cancer, and passed away at age 17 after two and a half grueling years of struggle.

Baruch Cohen loved his daughter with a fierce intensity, and he mourned her equally intensely — to the point where he thought he might never recover. But grieving is a process, and over the past 14 years he learned a lot about healing — what helped him, what brought him down, what his triggers were. A former avreich, he sought comfort and validation in Torah sources, and found much that spoke to him. The result is a new book, Grieving and Healing, a collection of divrei Torah and his own insights that are his offering to anyone who’s suffered a loss.

Nothing Prepares You

Born into a Modern Orthodox family in Far Rockaway, Cohen wasn’t sheltered from rough living or family tragedy. His father, Rabbi Dr. Samuel Cohen, headed the Jewish National Fund, but passed away at the relatively young age of 66.

“My parents were old-school religious Zionists,” he relates.

His mother, a Holocaust survivor descended from the Hager family of Vizhnitz, would later remarry Rabbi Berel Wein (she was nifteres this past January). “Rabbi Baruch Chait’s father was the rav of our shul,”he adds.

Baruch was sent to Camp Torah Vodaath, where he became inspired by learning. He spent six years there before marrying his wife Adina (n?e Mandelbaum, a descendant of the family who built the house that became the Mandelbaum Gate). After marrying, he enrolled in kollel at Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim while earning a degree at Queens College at night.

“I always had a bug for the law,” he says. “In beis medrash we were only allowed to read the Wall Street Journal, but I’d read the New York Times at college, and sometimes go to the courthouses in Lower Manhattan to observe.”

He went for his law degree at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, which he describes as similar to NYU. He clerked for judges, worked for a Wall Street firm, and eventually segued from bankruptcy cases to business and civil law and trial litigation.

“I learned to fine-tune my speaking skills, learned how to address a jury,” he recounts. “I am aggressive, but not abrasive. I aim to be confident without being arrogant.”

By 2001, he seemed to have achieved the perfect upwardly mobile life. He had moved into his current office, bought himself a house in Hancock Park, and had four beautiful children. Just one day before 9/11, however, his family found themselves reeling from their own personal catastrophe: Hindy was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare and aggressive pediatric cancer. At the time, Hindy was a student in Bais Yaakov of Los Angeles. Photos depict a sweet-faced teenager with dark hair and her father’s blue eyes.

“She was a normal, terrific frum kid,” her father says. “She loved school, she loved her family. She had many friends who visited all the time. During the times she was out of the hospital, they’d constantly go out for coffee, go shopping at the mall. She didn’t want to draw attention to herself or be a ‘chesed project.’ ”

Having a child with cancer rudely catapulted the family into a brand-new terrifying mental space.

“It was Gehinnom, a terrible nisayon,” Cohen says. “Suddenly you’re breathing a different oxygen than everyone else. I used to flip past the Chai Lifeline ads in magazines with pictures of sick kids — I never imagined it could concern me! I used to go to Disneyland, and just see balloons and cartoon characters. But once I went there with a child in a wheelchair, I only saw the sick kids.”

Cohen’s wife Adina would stay at the hospital during the week with Hindy, while Cohen would visit after work and spend Shabbos with her. They’d sing zemiros together on Friday nights, and make Shabbos parties on Saturday afternoons with Chai Lifeline nosh, often sharing with the hospital staff and friends who walked over to see her. Hindy loved hearing stories about her father’s trial victories and setbacks, and having her father read her news and columns from Jewish newspapers. Both enjoyed the lively DMCs those articles would provoke.

“During the week, I would save hysterical jokes to share with Hindy on Shabbos,” Cohen says. “She loved a good laugh, and would try to guess the punch lines. Sometimes we’d watch old ‘I Love Lucy’ clips, and she’d giggle early into the episode as she anticipated the comic situation about to unfold.”

Rabbi Hershy Ten from Bikur Cholim walked many miles to visit them every single Shabbos, and Hindy always enjoyed his funny, entertaining company. “Her eyes would light up when he came,” Cohen says. “He was the perfect blend of optimism and realism.”

Cohen says he himself got through their ordeal by assembling a “dream team” for himself, a Rolodex of top rabbanim and advisors. No one rav could be all-purpose in their situation; they needed one rav who was good at empathy, another who could give medical guidance, yet another to pasken on other issues.

“My ‘team’ was a lifeline,” he says.

He kept up his law practice even while Hindy was sick, having seen other families who gave up jobs and went into bankruptcy in similar situations, and/or suffered serious shalom bayis problems.

“It kept me sane,” he admits.

But he and his wife barely saw each other during the months Hindy was sick. With three other children at home, they took shifts in the hospital, and were obliged to accept help from Chai Lifeline and Bikur Cholim. He tried not to let his brain go into fast-forward mode, knowing that fear is an adversary that could cripple him at a time his family could ill afford for him to collapse.

Dashed Hopes

Fifteen years ago, he says, people were still whispering “yenneh machlah” rather than calling cancer by its name. A well-intentioned person suggested that to help his daughter’s refuah, he should do a chesbon hanefesh, to uproot any aveirahs or character flaws he had.

“That hurt me,” he says. “It’s not a healthy suggestion, either psychologically or religiously, for someone emotionally compromised by trauma.”

He wasn’t the type to start running around to rabbis and rebbes for brachos.

“I’m Litvish. I’m not into kabbalah,” he says. But he did join parent support groups from Chai Lifeline, and found them helpful.

Hindy herself was never a complainer, and held on to her emunah peshutah throughout her ordeal, always conscientious to express deep hakaras hatov to the nurses and doctors.

“She got that solid emunah from my wife,” Cohen declares.

At first, it looked like their positive outlook was justified: Hindy went into remission after the first course of treatment at Children’s Hospital, lasting about nine months.

“It is hard to describe the simchah in our home and at school when Hindy returned at the very end of tenth grade after her first bout with cancer,” Cohen would later write. “Teachers and classmates [were] running up to her, hugging her and kissing her.”

But Ewing’s sarcoma often comes back, even after a decade. In Hindy’s case, it returned just a year later, and Hindy missed out on the end of 11th grade and the first half of her senior year. Then a CT scan in January showed her to be cancer-free, and she was able to go back to school in February to the rejoicing of her family and friends.

“It was as if Adar had come early,” Cohen recalls.

But their joy was premature. In mid-February, doctors determined that the tumor had returned, and informed Baruch and Adina that the situation was critical — and terminal. Hindy herself knew the tumor was back, although she didn’t know just how critical things were. She was having trouble breathing, but managed to attend her brother Yehuda’s bar mitzvah. She had had her heart set on going to the Bais Yaakov Shabbaton in Malibu, and with heavy hearts her parents selflessly let her attend, despite their own longing to spend every last moment with her.

The Cohens had prayed that Hindy’s end not be painful or prolonged, and Hashem listened: He sent her a misas neshikah. The following week, on Rosh Chodesh Adar, January 23, Hindy’s neshamah left This World. Her parents had hoped one day to accompany her to the chuppah in a white gown; now they accompanied her to Olam HaEmes, in white shrouds.

Valley of the Shadow

Shivah is always painful, but Cohen found that many well-intentioned but thoughtless people inadvertently twisted the knife in the wound. Himself overwrought and hypersensitive, bromides like “Ein milim, there are no words” grated on him. He didn’t want to hear, “Hashem only sends these sorts of tests to people who can handle them” (who said he was handling?), or, “You must be very special if Hashem chose you for this nisayon” (please, Hashem, make me less special!). People would shake their heads and cluck, “Life will never be the same,” condemning him to a lifetime of depression.

Nor was it helpful to hear hagiographic accounts of gedolim who lost cherished family members over Shabbos, but didn’t let a single tear fall until after Havdalah.

“Baruch’s persona as a lawyer is aggressive, but it’s only a persona,” comments Rabbi Shlomo Einhorn, the rav of his shul. “One on one, he’s a very sensitive person.”

“How was I supposed to feel, reading those?” Cohen says. “Are we not supposed to have any emotions? Am I a lesser person because I’m devastated by my daughter’s death?”

He very much appreciated when Rabbi Label and Vivian Steinhardt flew in from New York to meet with his family. The Steinhardts had tragically lost their son Dovi, and established Ezras Dov to help bereaved families. Rabbi Steinhardt was a menahel in the mesivta of Chaim Berlin, and Cohen had been Dovi’s counselor when Dovi was a camper in Mogen Avraham.

“They communicated a healthy outlook on grief,” he says. “You can’t defer grief. Grief is there for a reason. If you try to defer it, the basketball will still be under the carpet. “

He didn’t go into denial — quite the opposite. “I fell into a black hole,” he says. “Depression was now my potential adversary.”

During the following months, he saw what helped him and what didn’t. It didn’t help when, as he broke down crying during davening, someone said to him, “You’re still with that?” On the other hand, a gentle squeeze on the shoulder by a friend as he sobbed under his tallis made him feel supported. A walk with a friend who didn’t say anything, just kept him company in a caring way, was helpful.

“That sort of validation was the key to healing,” he says. “My pain was very real. But Hashem wanted me to have it, so I know there must have been something there for me in the experience.”

He learned what events are painful triggers for him. “I still won’t go to a child’s funeral,” he says. “It’s too devastating. It takes me too long to recuperate.”

He went to events with other bereaved parents, finding them very helpful at the beginning. He saw different approaches to grief, learned from different therapists. After a while, however, those events produced “diminishing returns” for him, and the speeches became predictable.

Eventually he was able to move from “being pain” to “having pain,” as bereaved mother Sherri Mandell describes in her book The Blessing of a Broken Heart. The major turnaround, the moment the river changed course for him, was the epiphany that he had to come out of his own grief to help his family deal with their pain.

“That’s what started me on the path to healing,” he says. “I saw the toll on the others, and that pushed me to be stronger for them.”

Around that time, while in shul on a Friday night and feeling low, he started paying attention to the words of Kabbalas Shabbos. “Rav lach sheves b’eimek habacha — Too long have you dwelt in the valley of tears,” the men sang, and the words seemed to speak directly to him.

He was finally tired of being stuck in a ditch, and tired of reading books about tragedy. “I’m a lawyer. I’m used to creating trial strategies and preparing for a litigation fight,” he says. “But here I found myself in the ultimate fight, a fight with the yetzer hara.”

A fan of Sun Tzu’s classic, The Art of War, he knew the first principle: Know your enemy and know yourself. In his case, he knew his enemy to be competing, paralyzing emotions, and he needed to be strong and focused in his battle against them, like a true warrior. His new game plan was to seek counsel from the truly wise, our Torah sages.

“Baruch is a deep person and a product of his Chofetz Chaim background, in that he looks at everything through a Torah lens,” says his friend Rabbi Nechemia Langer, rav of Beis Medrash Shaare Torah in Los Angeles.

“I wanted to hear advice directly from Chazal,” Cohen says. “I started amassing a library of divrei Chazal, Tehillim, tefillah, and Torah insights on bereavement, looking for gems that would speak to me.”

He began collecting letters from great rabbanim and even secular writers about grief. For example, Rav Moshe Feinstein wrote a letter to Rav Shneur Kotler when the latter’s beloved son was niftar; even President Lincoln, who lost three children, wrote a sensitive letter about mourning to a bereaved mother who lost two sons in the Civil War.

Passages from Torah that he’d never paid attention to when things were going well now leapt off the page with question marks. Why don’t we hear about Yaakov crying for Rochel, although we are told Yaakov cried at other times, and we are told Avraham cried for Sarah? How did Aharon HaKohein’s wife react when her sons were consumed by fire? Why did Yaakov allow Yehudah to bring Binyamin to Yosef in Mitzrayim? (Because Yaakov knew Yehudah, also a bereaved parent, would understand what was as stake.)

Ironically, shortly before Hindy was diagnosed, Cohen developed a strange yen to learn the Shaar Habitachon section of the Chovos Halevavos. “I’d always avoided it when I was in Chofetz Chaim,” he avows. “But suddenly I felt interested. It’s as if Hashem wanted to send the refuah before the makkah.”

He found many of his own reactions addressed in Torah sources. For example, after Hindy was nifteres, he found it painful to watch other parents kiss their children in shul. Then he found a Chazal in Sefer Hachassidim that says one shouldn’t kiss his children in shul, because it could hurt the feelings of someone without a child.

“I felt validated,” he says.

Cohen’s rav, Rabbi Shlomo Einhorn of Kehilat Yavneh, gives him credit for tackling the loss head on. “So many people are struggling with loss, and books like When Bad Things Happen to Good People aren’t appropriate for the frum crowd. So they’re left with three options: leave religion, ignore the questions and get busy with life, or engage in questioning HaKadosh Baruch Hu through Torah.”

The bereavement process requires time and patience, and it’s life-altering. “Life now seems so tenuous, so fleeting,” Cohen remarks. “The secular ideals of money and fame lose all importance. As it is, every day we see in the news that someone can be on top of the world one day, and a pariah the next.

“We don’t think much about it, but Elisheva, Aharon HaKohein’s wife, also fell from a great height. Before she lost her sons, she was on top of the world. Her husband was the Kohein Gadol, her sons his priests. Her brother was Nachshon ben Aminadav. The day her sons died, she had five simchahs! We should never get too comfortable with our lives being ‘perfect.’ ”

Nowadays, when he goes to shul, he doesn’t look at the rich and famous; he seeks out the people in pain. He says he’s developed a special radar for them.

Eventually, he compiled many of the divrei Torah he’d found into a collection called Reb Yochanan’s Bone, which he printed up and distributed to friends and others he felt could benefit. (Rabi Yochanan lost ten children, and when the tenth died, he made a necklace out of a bone from that child’s little finger. He would wear it when he visited mourning parents to show them that they should not feel singled out for punishment by Hashem, since he himself, the gadol hador, had been similarly afflicted.)

As the years went on, Cohen was often called upon to speak at various functions. He speaks in his shul every year at the Seudah Shlishis before Hindy’s yahrtzeit, and the crowd has steadily grown so that now there’s usually standing room only. He attends the Bais Yaakov graduation and speaks while presenting an award he and his wife established in Hindy’s memory. It goes to a girl who, like Hindy, excels in good middos.

Another time, he was able to speak to a very high-profile group of bereaved parents in the secular world, household names in music, entertainment, and politics. One woman asked him, “Why aren’t you angry at G-d?”

He replied, “When you go through any difficult test, you can always think of ways it could be worse, but find simchah instead. You can’t forget all the good things G-d does for you even when one part of life is hard.”

“She was touched by that,” he remembers. “But to ask, ‘How could Hashem do this?’ is arrogance. Who are we to judge His decisions? It takes a certain humility to accept His decisions.”

Reaching Out Yet Further

Cohen began emerging from his grief when he realized he needed to be there for his family. And the steep climb upward was further aided by his desire to help other people as well. He wanted to use the Torah insights he’d gleaned along the way to help other bereaved parents learn the right hashfakos to deal with their challenge.

“Grief is one of the most-searched terms in Amazon,” he says. “It can be a rudderless boat. I wanted to give people healthy guidelines to navigate it.”

“What makes Baruch tick is his ability to inspire others,” says longtime Chofetz Chaim friend Rabbi Avrohom Stuhlberger. “Some people would have suppressed their memories [of a trauma] after a few years, but he retained the fire to channel his sorrow into strength.”

Cohen would send letters or poems to parents who had lost a child. Then he compiled his various hespedim, speeches, meditations, and Torah gems into a self-published book he entitled Grief and Healing through the Prism of Torah (sold through Amazon). Also included is his correspondence with the Sanz-Klausenberger Rebbe, in which the Rebbe compassionately speaks about the soul’s desire to return to its Maker, the impossibility of understanding Hashem’s ways, and the way his father, the previous Rebbe, coped with hardship and death in Auschwitz.

Another moving piece of writing in the collection was found on an American soldier, Colonel David (Mickey) Marcus, who died during the Israeli War of Independence. Marcus describes a ship leaving port for faraway lands, as a mashal for passing to the Next World. The people on shore cry as it departs; they’ll miss their loved ones on the boat, and don’t know when they’ll be reunited again. Although the ship seems to get smaller and smaller as it sails away, of course it remains the same size it always was. After a long voyage, it reaches a far-off shore in a foreign land. There, another set of people is waiting. “It’s arrived!” they cry joyfully.

A similarly encouraging perspective on death can be garnered from the excerpt from Rav Yechiel Michel Tukachinsky’s Gesher Hachaim, concepts that were later adapted into a song by Abie Rotenberg entitled “Conversation in the Womb.” Rav Tukachinsky describes twins in their mother’s womb, beginning their descent into this world. One twin, who’s comfortable in the womb and doesn’t believe in a world beyond it, doesn’t want to leave; he’s convinced it will be the end of him. The other, a baal emunah, tells him there’s another, amazing world beyond the womb, where they’ll walk freely and breathe and eat through their mouths.

The believer is born first, and the other twin hears shouting and crying. Now the next one is really terrified, convinced the “next world” means death! What he doesn’t understand is the shouts are happy cries of “Mazel tov.”

Cohen found inspiration from Rav Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the Rebbe of Piaseczna and rebbe of the Warsaw Ghetto. When the ghetto was about to be liquidated, Rav Shapira buried the manuscript of his writings with the plea they be taken to Eretz Yisrael if found after the war. The manuscript was indeed found and published as Aish Kodesh.

Cohen warmed to the idea that just because we “lose” something doesn’t mean it’s lost forever. And when he read Aish Kodesh, he was inspired by the discussion of a midrash in which Moshe Rabbeinu expressed a fear to Hashem: “Will I truly cease to be remembered when I die?” Hashem’s response, in brief, was that when the Jewish People carry out mitzvos, they will remember him. Any time we perform mitzvos on behalf of a departed loved one, especially mitzvos that were dear to them, it helps keep them alive both in This World and the Next.

Similarly, all these projects in Hindy’s zechus help keep the Cohen family connected to her. “I don’t like to say I ‘lost’ a daughter,” Cohen says. “She isn’t lost. I still have four children, three here and one in Shamayim. I’ll always be her abba.”

When the Cohens’ daughter Tali Hertz gave birth to a baby girl and named her Chaya Chana Hindy, it brought whole new levels of nechamah.

“Tali and her husband Yechiel told us the name with such sensitivity,” Cohen says. “Just to hear Hindy’s name said to the baby in a normal, loving manner is very healing. To see her name perpetuated is the ultimate gift.”

He adds that Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl lost five sons during the war, remarried in America, and had five more sons whom he named for the deceased ones. At the bris of the fifth son, he said, “Nekadeish b’shimchah b’olam,” the sons should be mekadeish Sheim Shamayim on earth like their namesakes in Shamayim.

It’s not easy to be shattered, Cohen says, but Hashem treasures broken luchos. A short chapter in his book discusses the Japanese art of kintsukoroi, in which broken pottery is repaired by bonding the shards together with lacquer mixed with gold, silver or platinum. The gleaming fault lines are evidence of an irreversible trauma that marked the object forever. But instead of trying to hide or disguise the damage, the Japanese transform the repair into art, creating a final product that is even more valuable than before.

“We always think about her [Hindy], but we continue on, with the ‘second set of Luchos’ even after our first set was broken and shattered,” Cohen writes in his book. “When we feel that our ‘set of Luchos’ are shattered, we need only to open our hearts to receive Hashem’s gift of a ‘second set of Luchos’ — the belief that joy can, and will, find a place in our lives again, with Luchos that will never be broken.” (Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 719)

https://mishpacha.com/whole-broken-vessels/

“Suddenly you’re breathing a different oxygen than everyone else. I used to flip past the Chai Lifeline ads in magazines with pictures of sick kids — I never imagined it could concern me!”

Baruch C. Cohen is a tall man with a commanding presence, the sonorous voice of a stage actor, and a trial lawyer’s way with words. His law office, on the ninth floor of a swanky professional building on Wilshire Drive, affords a sweeping view of Los Angeles, with downtown at one end and the Pacific Coast at the other. The walls are adorned with framed degrees, awards, and news articles in which he’s been featured.

Everything in this immaculate, gleaming office speaks to prestige and success, and Cohen presents as an alpha-male lawyer, an intense and forceful advocate who knows what he wants to achieve and will go after it tenaciously. He has been described by others as a “pit bull” in courtroom battles, and is equally aggressive about defending Israel’s right to exist, authoring a blog entitled American Trial Lawyers in Defense of Israel.

Yet despite his powerful personality, Cohen was brought to his knees some 14 years ago when tragedy struck his family. His oldest child, Hindy, was diagnosed with cancer, and passed away at age 17 after two and a half grueling years of struggle.

Baruch Cohen loved his daughter with a fierce intensity, and he mourned her equally intensely — to the point where he thought he might never recover. But grieving is a process, and over the past 14 years he learned a lot about healing — what helped him, what brought him down, what his triggers were. A former avreich, he sought comfort and validation in Torah sources, and found much that spoke to him. The result is a new book, Grieving and Healing, a collection of divrei Torah and his own insights that are his offering to anyone who’s suffered a loss.

Nothing Prepares You

Born into a Modern Orthodox family in Far Rockaway, Cohen wasn’t sheltered from rough living or family tragedy. His father, Rabbi Dr. Samuel Cohen, headed the Jewish National Fund, but passed away at the relatively young age of 66.

“My parents were old-school religious Zionists,” he relates.

His mother, a Holocaust survivor descended from the Hager family of Vizhnitz, would later remarry Rabbi Berel Wein (she was nifteres this past January). “Rabbi Baruch Chait’s father was the rav of our shul,”he adds.

Baruch was sent to Camp Torah Vodaath, where he became inspired by learning. He spent six years there before marrying his wife Adina (n?e Mandelbaum, a descendant of the family who built the house that became the Mandelbaum Gate). After marrying, he enrolled in kollel at Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim while earning a degree at Queens College at night.

“I always had a bug for the law,” he says. “In beis medrash we were only allowed to read the Wall Street Journal, but I’d read the New York Times at college, and sometimes go to the courthouses in Lower Manhattan to observe.”

He went for his law degree at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, which he describes as similar to NYU. He clerked for judges, worked for a Wall Street firm, and eventually segued from bankruptcy cases to business and civil law and trial litigation.

“I learned to fine-tune my speaking skills, learned how to address a jury,” he recounts. “I am aggressive, but not abrasive. I aim to be confident without being arrogant.”

By 2001, he seemed to have achieved the perfect upwardly mobile life. He had moved into his current office, bought himself a house in Hancock Park, and had four beautiful children. Just one day before 9/11, however, his family found themselves reeling from their own personal catastrophe: Hindy was diagnosed with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare and aggressive pediatric cancer. At the time, Hindy was a student in Bais Yaakov of Los Angeles. Photos depict a sweet-faced teenager with dark hair and her father’s blue eyes.

“She was a normal, terrific frum kid,” her father says. “She loved school, she loved her family. She had many friends who visited all the time. During the times she was out of the hospital, they’d constantly go out for coffee, go shopping at the mall. She didn’t want to draw attention to herself or be a ‘chesed project.’ ”

Having a child with cancer rudely catapulted the family into a brand-new terrifying mental space.

“It was Gehinnom, a terrible nisayon,” Cohen says. “Suddenly you’re breathing a different oxygen than everyone else. I used to flip past the Chai Lifeline ads in magazines with pictures of sick kids — I never imagined it could concern me! I used to go to Disneyland, and just see balloons and cartoon characters. But once I went there with a child in a wheelchair, I only saw the sick kids.”

Cohen’s wife Adina would stay at the hospital during the week with Hindy, while Cohen would visit after work and spend Shabbos with her. They’d sing zemiros together on Friday nights, and make Shabbos parties on Saturday afternoons with Chai Lifeline nosh, often sharing with the hospital staff and friends who walked over to see her. Hindy loved hearing stories about her father’s trial victories and setbacks, and having her father read her news and columns from Jewish newspapers. Both enjoyed the lively DMCs those articles would provoke.

“During the week, I would save hysterical jokes to share with Hindy on Shabbos,” Cohen says. “She loved a good laugh, and would try to guess the punch lines. Sometimes we’d watch old ‘I Love Lucy’ clips, and she’d giggle early into the episode as she anticipated the comic situation about to unfold.”

Rabbi Hershy Ten from Bikur Cholim walked many miles to visit them every single Shabbos, and Hindy always enjoyed his funny, entertaining company. “Her eyes would light up when he came,” Cohen says. “He was the perfect blend of optimism and realism.”

Cohen says he himself got through their ordeal by assembling a “dream team” for himself, a Rolodex of top rabbanim and advisors. No one rav could be all-purpose in their situation; they needed one rav who was good at empathy, another who could give medical guidance, yet another to pasken on other issues.

“My ‘team’ was a lifeline,” he says.

He kept up his law practice even while Hindy was sick, having seen other families who gave up jobs and went into bankruptcy in similar situations, and/or suffered serious shalom bayis problems.

“It kept me sane,” he admits.

But he and his wife barely saw each other during the months Hindy was sick. With three other children at home, they took shifts in the hospital, and were obliged to accept help from Chai Lifeline and Bikur Cholim. He tried not to let his brain go into fast-forward mode, knowing that fear is an adversary that could cripple him at a time his family could ill afford for him to collapse.

Dashed Hopes

Fifteen years ago, he says, people were still whispering “yenneh machlah” rather than calling cancer by its name. A well-intentioned person suggested that to help his daughter’s refuah, he should do a chesbon hanefesh, to uproot any aveirahs or character flaws he had.

“That hurt me,” he says. “It’s not a healthy suggestion, either psychologically or religiously, for someone emotionally compromised by trauma.”

He wasn’t the type to start running around to rabbis and rebbes for brachos.

“I’m Litvish. I’m not into kabbalah,” he says. But he did join parent support groups from Chai Lifeline, and found them helpful.

Hindy herself was never a complainer, and held on to her emunah peshutah throughout her ordeal, always conscientious to express deep hakaras hatov to the nurses and doctors.

“She got that solid emunah from my wife,” Cohen declares.

At first, it looked like their positive outlook was justified: Hindy went into remission after the first course of treatment at Children’s Hospital, lasting about nine months.

“It is hard to describe the simchah in our home and at school when Hindy returned at the very end of tenth grade after her first bout with cancer,” Cohen would later write. “Teachers and classmates [were] running up to her, hugging her and kissing her.”

But Ewing’s sarcoma often comes back, even after a decade. In Hindy’s case, it returned just a year later, and Hindy missed out on the end of 11th grade and the first half of her senior year. Then a CT scan in January showed her to be cancer-free, and she was able to go back to school in February to the rejoicing of her family and friends.

“It was as if Adar had come early,” Cohen recalls.

But their joy was premature. In mid-February, doctors determined that the tumor had returned, and informed Baruch and Adina that the situation was critical — and terminal. Hindy herself knew the tumor was back, although she didn’t know just how critical things were. She was having trouble breathing, but managed to attend her brother Yehuda’s bar mitzvah. She had had her heart set on going to the Bais Yaakov Shabbaton in Malibu, and with heavy hearts her parents selflessly let her attend, despite their own longing to spend every last moment with her.

The Cohens had prayed that Hindy’s end not be painful or prolonged, and Hashem listened: He sent her a misas neshikah. The following week, on Rosh Chodesh Adar, January 23, Hindy’s neshamah left This World. Her parents had hoped one day to accompany her to the chuppah in a white gown; now they accompanied her to Olam HaEmes, in white shrouds.

Valley of the Shadow

Shivah is always painful, but Cohen found that many well-intentioned but thoughtless people inadvertently twisted the knife in the wound. Himself overwrought and hypersensitive, bromides like “Ein milim, there are no words” grated on him. He didn’t want to hear, “Hashem only sends these sorts of tests to people who can handle them” (who said he was handling?), or, “You must be very special if Hashem chose you for this nisayon” (please, Hashem, make me less special!). People would shake their heads and cluck, “Life will never be the same,” condemning him to a lifetime of depression.

Nor was it helpful to hear hagiographic accounts of gedolim who lost cherished family members over Shabbos, but didn’t let a single tear fall until after Havdalah.

“Baruch’s persona as a lawyer is aggressive, but it’s only a persona,” comments Rabbi Shlomo Einhorn, the rav of his shul. “One on one, he’s a very sensitive person.”

“How was I supposed to feel, reading those?” Cohen says. “Are we not supposed to have any emotions? Am I a lesser person because I’m devastated by my daughter’s death?”

He very much appreciated when Rabbi Label and Vivian Steinhardt flew in from New York to meet with his family. The Steinhardts had tragically lost their son Dovi, and established Ezras Dov to help bereaved families. Rabbi Steinhardt was a menahel in the mesivta of Chaim Berlin, and Cohen had been Dovi’s counselor when Dovi was a camper in Mogen Avraham.

“They communicated a healthy outlook on grief,” he says. “You can’t defer grief. Grief is there for a reason. If you try to defer it, the basketball will still be under the carpet. “

He didn’t go into denial — quite the opposite. “I fell into a black hole,” he says. “Depression was now my potential adversary.”

During the following months, he saw what helped him and what didn’t. It didn’t help when, as he broke down crying during davening, someone said to him, “You’re still with that?” On the other hand, a gentle squeeze on the shoulder by a friend as he sobbed under his tallis made him feel supported. A walk with a friend who didn’t say anything, just kept him company in a caring way, was helpful.

“That sort of validation was the key to healing,” he says. “My pain was very real. But Hashem wanted me to have it, so I know there must have been something there for me in the experience.”

He learned what events are painful triggers for him. “I still won’t go to a child’s funeral,” he says. “It’s too devastating. It takes me too long to recuperate.”

He went to events with other bereaved parents, finding them very helpful at the beginning. He saw different approaches to grief, learned from different therapists. After a while, however, those events produced “diminishing returns” for him, and the speeches became predictable.

Eventually he was able to move from “being pain” to “having pain,” as bereaved mother Sherri Mandell describes in her book The Blessing of a Broken Heart. The major turnaround, the moment the river changed course for him, was the epiphany that he had to come out of his own grief to help his family deal with their pain.

“That’s what started me on the path to healing,” he says. “I saw the toll on the others, and that pushed me to be stronger for them.”

Around that time, while in shul on a Friday night and feeling low, he started paying attention to the words of Kabbalas Shabbos. “Rav lach sheves b’eimek habacha — Too long have you dwelt in the valley of tears,” the men sang, and the words seemed to speak directly to him.

He was finally tired of being stuck in a ditch, and tired of reading books about tragedy. “I’m a lawyer. I’m used to creating trial strategies and preparing for a litigation fight,” he says. “But here I found myself in the ultimate fight, a fight with the yetzer hara.”

A fan of Sun Tzu’s classic, The Art of War, he knew the first principle: Know your enemy and know yourself. In his case, he knew his enemy to be competing, paralyzing emotions, and he needed to be strong and focused in his battle against them, like a true warrior. His new game plan was to seek counsel from the truly wise, our Torah sages.

“Baruch is a deep person and a product of his Chofetz Chaim background, in that he looks at everything through a Torah lens,” says his friend Rabbi Nechemia Langer, rav of Beis Medrash Shaare Torah in Los Angeles.

“I wanted to hear advice directly from Chazal,” Cohen says. “I started amassing a library of divrei Chazal, Tehillim, tefillah, and Torah insights on bereavement, looking for gems that would speak to me.”

He began collecting letters from great rabbanim and even secular writers about grief. For example, Rav Moshe Feinstein wrote a letter to Rav Shneur Kotler when the latter’s beloved son was niftar; even President Lincoln, who lost three children, wrote a sensitive letter about mourning to a bereaved mother who lost two sons in the Civil War.

Passages from Torah that he’d never paid attention to when things were going well now leapt off the page with question marks. Why don’t we hear about Yaakov crying for Rochel, although we are told Yaakov cried at other times, and we are told Avraham cried for Sarah? How did Aharon HaKohein’s wife react when her sons were consumed by fire? Why did Yaakov allow Yehudah to bring Binyamin to Yosef in Mitzrayim? (Because Yaakov knew Yehudah, also a bereaved parent, would understand what was as stake.)

Ironically, shortly before Hindy was diagnosed, Cohen developed a strange yen to learn the Shaar Habitachon section of the Chovos Halevavos. “I’d always avoided it when I was in Chofetz Chaim,” he avows. “But suddenly I felt interested. It’s as if Hashem wanted to send the refuah before the makkah.”

He found many of his own reactions addressed in Torah sources. For example, after Hindy was nifteres, he found it painful to watch other parents kiss their children in shul. Then he found a Chazal in Sefer Hachassidim that says one shouldn’t kiss his children in shul, because it could hurt the feelings of someone without a child.

“I felt validated,” he says.

Cohen’s rav, Rabbi Shlomo Einhorn of Kehilat Yavneh, gives him credit for tackling the loss head on. “So many people are struggling with loss, and books like When Bad Things Happen to Good People aren’t appropriate for the frum crowd. So they’re left with three options: leave religion, ignore the questions and get busy with life, or engage in questioning HaKadosh Baruch Hu through Torah.”

The bereavement process requires time and patience, and it’s life-altering. “Life now seems so tenuous, so fleeting,” Cohen remarks. “The secular ideals of money and fame lose all importance. As it is, every day we see in the news that someone can be on top of the world one day, and a pariah the next.

“We don’t think much about it, but Elisheva, Aharon HaKohein’s wife, also fell from a great height. Before she lost her sons, she was on top of the world. Her husband was the Kohein Gadol, her sons his priests. Her brother was Nachshon ben Aminadav. The day her sons died, she had five simchahs! We should never get too comfortable with our lives being ‘perfect.’ ”

Nowadays, when he goes to shul, he doesn’t look at the rich and famous; he seeks out the people in pain. He says he’s developed a special radar for them.

Eventually, he compiled many of the divrei Torah he’d found into a collection called Reb Yochanan’s Bone, which he printed up and distributed to friends and others he felt could benefit. (Rabi Yochanan lost ten children, and when the tenth died, he made a necklace out of a bone from that child’s little finger. He would wear it when he visited mourning parents to show them that they should not feel singled out for punishment by Hashem, since he himself, the gadol hador, had been similarly afflicted.)

As the years went on, Cohen was often called upon to speak at various functions. He speaks in his shul every year at the Seudah Shlishis before Hindy’s yahrtzeit, and the crowd has steadily grown so that now there’s usually standing room only. He attends the Bais Yaakov graduation and speaks while presenting an award he and his wife established in Hindy’s memory. It goes to a girl who, like Hindy, excels in good middos.

Another time, he was able to speak to a very high-profile group of bereaved parents in the secular world, household names in music, entertainment, and politics. One woman asked him, “Why aren’t you angry at G-d?”

He replied, “When you go through any difficult test, you can always think of ways it could be worse, but find simchah instead. You can’t forget all the good things G-d does for you even when one part of life is hard.”

“She was touched by that,” he remembers. “But to ask, ‘How could Hashem do this?’ is arrogance. Who are we to judge His decisions? It takes a certain humility to accept His decisions.”

Reaching Out Yet Further

Cohen began emerging from his grief when he realized he needed to be there for his family. And the steep climb upward was further aided by his desire to help other people as well. He wanted to use the Torah insights he’d gleaned along the way to help other bereaved parents learn the right hashfakos to deal with their challenge.

“Grief is one of the most-searched terms in Amazon,” he says. “It can be a rudderless boat. I wanted to give people healthy guidelines to navigate it.”

“What makes Baruch tick is his ability to inspire others,” says longtime Chofetz Chaim friend Rabbi Avrohom Stuhlberger. “Some people would have suppressed their memories [of a trauma] after a few years, but he retained the fire to channel his sorrow into strength.”

Cohen would send letters or poems to parents who had lost a child. Then he compiled his various hespedim, speeches, meditations, and Torah gems into a self-published book he entitled Grief and Healing through the Prism of Torah (sold through Amazon). Also included is his correspondence with the Sanz-Klausenberger Rebbe, in which the Rebbe compassionately speaks about the soul’s desire to return to its Maker, the impossibility of understanding Hashem’s ways, and the way his father, the previous Rebbe, coped with hardship and death in Auschwitz.

Another moving piece of writing in the collection was found on an American soldier, Colonel David (Mickey) Marcus, who died during the Israeli War of Independence. Marcus describes a ship leaving port for faraway lands, as a mashal for passing to the Next World. The people on shore cry as it departs; they’ll miss their loved ones on the boat, and don’t know when they’ll be reunited again. Although the ship seems to get smaller and smaller as it sails away, of course it remains the same size it always was. After a long voyage, it reaches a far-off shore in a foreign land. There, another set of people is waiting. “It’s arrived!” they cry joyfully.

A similarly encouraging perspective on death can be garnered from the excerpt from Rav Yechiel Michel Tukachinsky’s Gesher Hachaim, concepts that were later adapted into a song by Abie Rotenberg entitled “Conversation in the Womb.” Rav Tukachinsky describes twins in their mother’s womb, beginning their descent into this world. One twin, who’s comfortable in the womb and doesn’t believe in a world beyond it, doesn’t want to leave; he’s convinced it will be the end of him. The other, a baal emunah, tells him there’s another, amazing world beyond the womb, where they’ll walk freely and breathe and eat through their mouths.

The believer is born first, and the other twin hears shouting and crying. Now the next one is really terrified, convinced the “next world” means death! What he doesn’t understand is the shouts are happy cries of “Mazel tov.”

Cohen found inspiration from Rav Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the Rebbe of Piaseczna and rebbe of the Warsaw Ghetto. When the ghetto was about to be liquidated, Rav Shapira buried the manuscript of his writings with the plea they be taken to Eretz Yisrael if found after the war. The manuscript was indeed found and published as Aish Kodesh.

Cohen warmed to the idea that just because we “lose” something doesn’t mean it’s lost forever. And when he read Aish Kodesh, he was inspired by the discussion of a midrash in which Moshe Rabbeinu expressed a fear to Hashem: “Will I truly cease to be remembered when I die?” Hashem’s response, in brief, was that when the Jewish People carry out mitzvos, they will remember him. Any time we perform mitzvos on behalf of a departed loved one, especially mitzvos that were dear to them, it helps keep them alive both in This World and the Next.

Similarly, all these projects in Hindy’s zechus help keep the Cohen family connected to her. “I don’t like to say I ‘lost’ a daughter,” Cohen says. “She isn’t lost. I still have four children, three here and one in Shamayim. I’ll always be her abba.”

When the Cohens’ daughter Tali Hertz gave birth to a baby girl and named her Chaya Chana Hindy, it brought whole new levels of nechamah.

“Tali and her husband Yechiel told us the name with such sensitivity,” Cohen says. “Just to hear Hindy’s name said to the baby in a normal, loving manner is very healing. To see her name perpetuated is the ultimate gift.”

He adds that Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl lost five sons during the war, remarried in America, and had five more sons whom he named for the deceased ones. At the bris of the fifth son, he said, “Nekadeish b’shimchah b’olam,” the sons should be mekadeish Sheim Shamayim on earth like their namesakes in Shamayim.

It’s not easy to be shattered, Cohen says, but Hashem treasures broken luchos. A short chapter in his book discusses the Japanese art of kintsukoroi, in which broken pottery is repaired by bonding the shards together with lacquer mixed with gold, silver or platinum. The gleaming fault lines are evidence of an irreversible trauma that marked the object forever. But instead of trying to hide or disguise the damage, the Japanese transform the repair into art, creating a final product that is even more valuable than before.

“We always think about her [Hindy], but we continue on, with the ‘second set of Luchos’ even after our first set was broken and shattered,” Cohen writes in his book. “When we feel that our ‘set of Luchos’ are shattered, we need only to open our hearts to receive Hashem’s gift of a ‘second set of Luchos’ — the belief that joy can, and will, find a place in our lives again, with Luchos that will never be broken.” (Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 719)

https://mishpacha.com/whole-broken-vessels/

Labels:

Baruch C. Cohen,

Hindy Cohen

WARRIOR FOR THE JEWISH PEOPLE

In online videos, in speeches across the United States, on the streets of Jerusalem, Ari Fuld, 45, was a verbal warrior, loudly proclaiming his truth: Hashem gave Eretz Yisrael to the Jewish People, there was never a Palestinian state, the lies spread about Jews and Israel are a blood libel that should be vigorously fought at each and every moment, and whenever the opportunity arises.

In his final days, before he was brutally stabbed in the back by a 17-year-old Palestinian terrorist at an Efrat mall, Fuld, married and the father of four, was living his truth. On the day of his murder, he had visited the Western Wall and taken a video of thousands of Jews chanting Selichos. On the Shabbos before his murder, in an online parshah video on parshas Vayelech, Fuld explained Moshe Rabbeinu’s parting words to Klal Yisrael. Moshe could no longer “go and come” and he could not enter the land, he explained, not because he was old and enfeebled and not because he was no longer capable, but because HaKadosh Baruch Hu had proclaimed it as such; he had fulfilled his mission. Moshe’s time was over. And sadly, so was Ari’s.

Fuld’s murder touched the Anglo community in Israel deeply, as evidenced by the thousands of people who stayed up to the wee hours of the morning to pay their last respects in Kfar Etzion. As the family made its way to the cemetery, winding their way through the huge crowds of well-wishers from every stripe of Israeli society, mourners sang songs of comfort — “Avinu Malkeinu,” “Acheinu,” “Chamol al Maasecha.” At the shivah house, a stream of well-wishers visited a stricken family as rabbanim and friends offered words of sympathy and support.

As Ari lived, he died. Fuld, who was a third-degree black belt in karate and had taught others how to defend themselves against knife attacks, furiously attacked his stabber, landing a right cross and then running after his killer and shooting him before collapsing in a pool of blood.

In the two weeks since his murder, there has been an outpouring of grief and sadness for a man who many describe as a warrior for the Jewish People.

Josh Hasten, who met Fuld about eight years ago in Efrat, described Ari as a gentle giant, someone who was most in his element when he was defending the nation he loved. Hasten, who is the international spokesperson for Gush Etzion, remembered that a few months ago, when rockets were raining down on Sderot and the surrounding communities, Fuld drove there to aid the residents. “The normal reaction would be to run away, but he went down there davka to show support,” Hasten said.

Fuld, who made aliyah in 1994 and served in the Second Lebanon War, was the assistant director of Standing Together, a nonprofit group that delivers food, clothes, and other necessities to soldiers. About three weeks ago, Hasten got a call from Ari. He was on his way to Chevron to deliver ice packs to soldiers on a sweltering summer day. Other times, Fuld would show up at a base with pizzas and a smile.

Avi Abelow, who grew up with Fuld and attended elementary school with him at SAR Academy in Riverdale, the Bronx, remembers Ari as a spirited kid who would sometimes end up in the principal’s office — an office occupied by his father, well-known educator Rabbi Yonah Fuld. The pair later made aliyah at around the same time, and ended up settling in Efrat. For the past 15 years, Abelow has been Fuld’s neighbor, and the person he sat next to at shul.

“Ari, like his name, was a lion,” said Abelow, CEO of 12 Tribes Films, a company that makes Jewish-themed films and videos. “He was a fighter for truth in the online battle for Israel — very strong, very in your face, very emesdig. That was Ari the fighter. And you saw that in his last moments, even after he was stabbed and was supposed to be dead, his neshamah gave him the strength to [chase after his attacker]. Normal people don’t do that.”

Abelow believes that the huge outpouring of support for Fuld since his death is a recognition that his friend’s words and deeds reached further than many had suspected. “Ari had an inner truth that he stuck to — not just telling the truth but living the truth. Whatever cause he was working on, [he had] that overarching persona of emes that really came through no matter where he was or who he was with. Everyone was treated equally with respect and everyone felt that.”

Los Angeles attorney Baruch Cohen, who was featured in Mishpacha in July about his new book, Grieving and Healing, said Fuld first contacted him a few years ago out of the blue. Cohen maintains a website, American Trial Attorneys in Defense of Israel, and Fuld wrote to tell him how impressed he was that a chareidi Jew was expressing such pro-Israel views.

“He was not surprised but fascinated to find a soul brother in L.A.,” Cohen explained in a telephone interview. “Someone who has not made aliyah, but whose heart is in Israel.”

After Cohen got to know Fuld, he said he felt as if the two were like “twins separated at birth.” Whenever Fuld visited Los Angeles, the two would meet, and Cohen would walk away with “great chizuk.”

Cohen was especially impressed with Fuld’s bitachon, his sense of trust in HaKadosh Baruch Hu. Cohen retells a now well-known story about Fuld: that he carried in his tallis bag a piece of shrapnel that hit him in the Second Lebanon War. As the story goes, Fuld and his comrades were on the front lines. A couple of soldiers from his platoon were hit by fire and the commander told Fuld and others to bring them to safety before the enemy could take them as prisoners of war. Fuld leaped into the line of fire and brought back the bloodied soldiers. In the intervening minutes, the position that Fuld had been occupying was hit by missiles. If he had remained at his post, Fuld would have been mortally wounded. And not only that, a piece of shrapnel had penetrated his vest while he was on his rescue mission, but miraculously had gone no further.

“He would run toward tragedy to save lives, when the natural tendency is to run away,” Cohen said. “He had unconditional love for every chayal, and he [considered it an] honor to sacrifice [his] life to support his brothers and sisters in Israel.”

Cohen said Fuld’s bitachon and sense of service to Klal Yisrael was so strong that he “felt like a monkey” in his presence. “It wasn’t lip service,” he said. “This guy resonated this message; it was in his bones. It was the greatest mussar shmuess talking to this guy. [He was] a foundation of chizuk, a flow of ahavas Yisrael. When you encounter greatness like this, it charges your battery. He was a profoundly religious person.”