"We shall destroy Israel and its inhabitants," declared Palestine Liberation Organization leader Ahmad al-Shuqayri. "As for the survivors -- if there are any -- the boats are ready to deport them." A half-million Arab soldiers and more than 5,000 tanks converged on Israel from every direction, including the West Bank, then part of Jordan. Their plans called for obliterating Israel's army, conquering the country, and killing large numbers of civilians. Iraqi President Abdul Rahman Arif said the Arab goal was to wipe Israel off the map: "We shall, God willing, meet in Tel Aviv and Haifa."

This was the fate awaiting Israel on June 4, 1967. Many Israelis feverishly dug trenches and filled sandbags, while others secretly dug 10,000 graves for the presumed victims. Some 14,000 hospital beds were arranged and gas masks distributed to the civilian population. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) prepared to launch a pre-emptive strike to neutralize Egypt, the most powerful Arab state, but the threat of invasion by other Arab armies remained.

Israel's borders at the time were demarcated by the armistice lines established at the end of Israel's war of independence 18 years earlier. These lines left Israel a mere 9 miles wide at its most populous area. Israelis faced mountains to the east and the sea to their backs and, in West Jerusalem, were virtually surrounded by hostile forces. In 1948, Arab troops nearly cut the country in half at its narrow waist and laid siege to Jerusalem, depriving 100,000 Jews of food and water.

The Arabs readied to strike -- but Israel did not wait. "We will suffer many losses, but we have no other choice," explained IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin. The next morning, on June 5, Israeli jets and tanks launched a surprise attack against Egypt, destroying 204 of its planes in the first half-hour. By the end of the first morning of fighting, the Israeli Air Force had destroyed 286 of Egypt's 420 combat aircraft, 13 air bases, and 23 radar stations and anti-aircraft sites. It was the most successful single operation in aerial military history.

But, as feared, other Arab forces attacked. Enemy planes struck Israeli cities along the narrow waist, including Hadera, Netanya, Kfar Saba, and the northern suburbs of Tel Aviv; and thousands of artillery shells fired from the West Bank pummeled greater Tel Aviv and West Jerusalem. Ground forces, meanwhile, moved to encircle Jerusalem's Jewish neighborhoods as they did in 1948.

In six days, Israel repelled these incursions and established secure boundaries. It drove the Egyptians from the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula, and the Syrians, who had also opened fire, from the Golan Heights. Most significantly, Israel replaced the indefensible armistice lines by reuniting Jerusalem and capturing the West Bank from Jordan.

The Six-Day War furnished Israel with the territory and permanence necessary for achieving peace with Egypt and Jordan. It transformed Jerusalem from a divided backwater into a thriving capital, free for the first time to adherents of all faiths. It reconnected the Jewish people to our ancestral homeland in Judea and Samaria, inspiring many thousands to move there. But it also made us aware that another people -- the Palestinians -- inhabited that land and that we would have to share it.

As early as the summer of 1967, Israel proposed autonomy for the Palestinians in the West Bank and later, in 2000 and 2008, full statehood. Unfortunately, Palestinian leaders rejected these offers. In 2005, Israel uprooted all 8,000 of its citizens living in Gaza, giving the Palestinians the opportunity for self-determination. Instead, they turned Gaza into a Hamas-run terrorist state that has launched thousands of rockets into Israel. Now, the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank intends to unilaterally declare statehood at the United Nations without making peace. It has also united with Gaza's Hamas regime, which demands Israel's destruction.

In spite of the Palestinians' record of rejection and violence, Israel remains committed to the vision of two states living side by side in peace. But peace is predicated on security and on our ability to defend ourselves if the peace breaks down. Such provisions are crucial in the Middle East, where the governments of Israel's neighbors might change tomorrow. As such, we seek the demilitarization of the Palestinian state as well as a long-term IDF presence along the Jordan River to prevent rocket smuggling, as has occurred in Gaza. Moreover, we need defensible borders to ensure that Israel will never again pose an attractive target for attack.

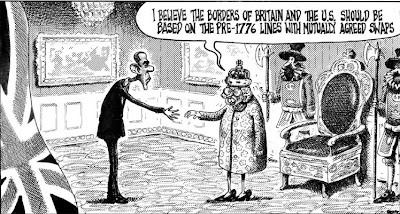

For this reason, Israel appreciates U.S. President Barack Obama's opposition to unilaterally declared Palestinian statehood and negotiations with Hamas, which refuses to recognize Israel, uphold previous peace agreements, and disavow terrorism. Similarly, we support the president's call for the nonmilitarization of any future Palestinian state that must be capable of assuming "security responsibility." In his recent address to a joint meeting of the U.S. Congress, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu affirmed the president's statement that the negotiated border will be "different than the one that existed on June 4, 1967."

Forty-four years after Arab forces sought to exploit the vulnerable armistice lines, it remains clear that Israel cannot return to those lines. And 44 years after the United Nations, through Resolution 242, indicated that Israel would not have to forfeit all of the captured territories and must achieve "secure and recognized boundaries," the unsecure and unrecognized armistice lines must not be revived. Israel's insistence on defensible borders is a prerequisite for peace and a safeguard against a return to the Arab illusions and Israeli fears of June 1967.